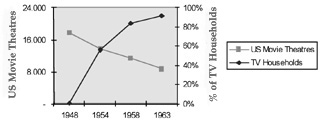

The Mad Mohel*: Will Cybersurgeons Clip Retail REITs? (*Mohel: one who performs the ritual circumcision. Yiddish, rhymes with Doyle.) by Mark Borsuk** The Real Estate Transformation Group Copyright Ó 1998.*** All Rights Reserved. Mark Borsuk. Submitted to the ICSC Research Quarterly, Summer 1998 issue. On Thursday, December 31, 1999, the Nine Dragon Gumi announced the purchase of We-B-Cheap, the nation’s largest computer retailer. The 150 store chain had been the darling of Wall Street for several years until in-store sales began falling precipitously in 1998. The big box superstore format, averaging 25,000 sq. ft., so successful earlier in the decade, was faltering. Paradoxically, We-B-Cheap’s overall sales continued to climb as a result of strong online buying. A chorus of top retail stock analysts called for a radical restructuring of We-B-Cheap’s sales channel matrix. Like other mass market retailers, We-B-Cheap had to contend with product price deflation induced by rapid technology change and the high fixed cost of operating stores as the primary sales channel. On Monday, January 4, 2000, We-B-Cheap, under new ownership, announced the settlement of the recently filed shareholders' suit. The company promised a massive restructuring. One month later it filed for bankruptcy. The debtor’s plan called for rejecting leases on one hundred stores and downsizing the remainder into 5,000 sq. ft. showrooms sans inventory. The Big Box REIT was one casualty of the bankruptcy. We-B-Cheap properties represented thirty percent of its portfolio. Launched in 1993, Big Box found the recipe for success by offering public ownership of retail stores with high-technology tenants. Pension funds and other institutional investors were the majority owners of its thinly traded shares. The bankruptcy filing set off a chain reaction and Big Box’s stock plummeted. Market insiders shorted the stock quickly, sinking it below the net asset value. Market wisdom held REITs were a good defensive stock, less inclined to decline in value if the overall market went south but unlikely to match gains in an up market. Unfortunately, the underlying theory was untested in the securitized world of property ownership that became so popular in the 1990s. The double whammy of information technology altering retail space demand and REIT shares falling below their presumed net asset value came as a horrible shock to investors. The "beta burn" forced them to make a hasty exit. Another repercussion of the bankruptcy was to freeze the issuance of new debt and equity for retail REITs, starving them for capital. Flush with offshore cash, the Gumi became Big Box’s largest shareholder and took control from the badly shaken management. On January 29, Big Box announced the soon to be vacant We-B-Cheap stores would become vertical pet cemeteries. Under the slogan "You Love’m, We Keep’m" the REIT could achieve profitability offering cubic space instead of square footage. Market historians recorded this as the first successful cybersurgery. Movie Theater Redux. Is it possible information technology could cause a decline in the demand for physical space? Yes, movie theaters are a case in point. They went into rapid decline from 1948 to 1963. The Chart depicts a 50 percent drop in theaters over fifteen years while the number of TV households rocketed from less than 1 percent to 90 percent. The tremendous popularity of TV, coming at the time of suburban migration, had a devastating impact on movie theaters. Could online buying impact retail property in a similar way? Information Technology Does Matter

Will Online Buying Shift Retail Space Demand? Any net decline in retail space requires customers to shop online and retailers to change their preference for the store as the primary sales channel. How likely is this to occur? Pushing the customer online. Use of the Internet has passed critical mass. Today, over 27 percent of households are wired1 and Web demographics mirror the population as a whole.2 By the year 2000, one-third of households will be online. This year 8 percent of adults will shop online3 and they will increase to 14 percent in 2000.4 Further, the gender gap is rapidly closing, with men comprising only 56 percent of users.5 More importantly, over the next several years women will likely emerge as the majority of buyers online for several reasons. First, the breadth and depth of products offered will become tailored to their needs. Second, online shopping will become a convenience channel. Shoppers will appreciate its time savings, price comparison abilities and lower costs. The Internet is changing the customer’s expectations about where to shop, when to shop and how to comparison shop. It is analogous to the impact of suburban migration on movie theaters. However, instead of moving from one physical location to another, the migration is from the store to cyberspace. Shopping and the shop are about to devolve. Pulling the retailer online.

Online buying will have its greatest impact on those merchants who sell commodity goods and services adding little value. Location, price and assortment are their strengths. A competitor can quickly compromise these advantages in cyberspace. Conversely, those merchants who add value in the store, offer experiential shopping, or whose goods and services require the customer’s physical presence will be initially immune from the trend. Practically speaking, the impact of online buying is like that of a retailer opening another store nearby: it cannibalizes sales. The belief that online buying is a reincarnation of catalog shopping ignores the unique benefits associated with online shopping. Unlike catalogs, the Internet will have an impact on space demand. Cannibalization is significant for retailers. Even a small shift in sales has a dramatic impact on store profitability. One panel at the 1997 ICSC Research Conference examined how sales cannibalization affects store performance. A participant noted that even a 7 percent shift in sales could lead to a 50 percent decline in store profitability. This means a marginal analysis is necessary to determine online shopping’s impact. Analyzing aggregate retailing numbers to discern trends will blind-side investors. Merchants also face a new form of price competition in cyberspace.6 One example is Books.com. It competes with Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble What makes this site so rewarding for customers is Books.com adjusts its price to the lowest competitor’s price to retain the sale. Online shoppers can also use intelligent agents or "bots" to search for the best price. The development of ever more sophisticated bots will pressure retailer margins. Retail Leasing Strategy in a Wired World. The Internet’s ability to cannibalize store sales requires mass market retailers to reformat the sales channel matrix. The introduction of the cyberchannel requires going from two dimensional (store/catalog) to three dimensional thinking. This is truly thinking outside the box. Leveraging the online presence will be at the expense of physical space. Leasing strategy must change to accommodate the new channel. Retailers will demand short term leases with multiple short term options and early termination rights for greater flexibility. First movers will likely pay a premium to obtain flexibility. However, continuing to expect higher rent from these retailers over time is unrealistic. Wall Street Loves Online Retailing. Simply comparing the market capitalization of Amazon.com (AMZN) to Barnes & Noble (BKS) affirms the market’s enthusiasm for online shopping. In early May, Amazon.com nearly equaled Barnes & Noble’s value. The fact that Barnes & Noble has over a thousand stores and Amazon.com has none is a very strong indication of how the market values location. Amazon.com is just one kind of stealth competitor sneaking up on traditional retailers and their stock prices. While Amazon.com represents a start-up, more seasoned stealth competitors will follow. Powerful companies like Wal-Mart with the capital and technological expertise to mount an aggressive campaign in cyberspace could readily invade other retailing niches. NetMarket, a membership site, is rapidly developing into a formidable competitor. Finally, manufactures who have sought to avoid channel conflict in the past could find it advantageous to bypass the retailer and reach customers directly. Events are coalescing to drive sales away from offline retailers and those not sufficiently exploiting the new channel. Wall Street stock and credit rating analysts are unlikely to reward the laggards. In addition, those retail executives granted stock options have to worry about sticking with stores. Thus, Wall Street will play an important role in influencing retailer decisions on space demand. The Unanticipated Consequences of Securitizing Retail Property. The securitization of retail real estate dramatically links trading and investment markets. The direct linkage removes the slack that existed to absorb regional, national and international shocks. Formerly, the private, long-term nature of the landlord-tenant relationship separated the markets. The trend to aggregate properties into securities subjects them to the systemic fragility of trading markets. But while many trading markets are global, giving them greater depth, they also display a greater tendency for normal accidents. Normal accidents come in many forms and occur randomly. A riot here, a war there or a financial collapse on some distant shore all have the capacity to destabilize share prices regardless of whether the event directly impacts the underlying asset. How is it possible for retail REITs to be detached from the vicissitudes of rapid technology change and chaotic events? Securitizing retail property also creates short selling opportunities. This was not possible with private property but now can be done online. Finally, securitizing property creates a new group of overseers who are unrelated to the risk of ownership. REIT equity analysts, credit rating agencies, the SEC and public relations firms are now all part of the value equation. Their opinions drive market expectations. Assessing the Risk of Online Buying. Online buying initially impacts commodity type goods and services retailers whose primary advantage is price, location and selection. The Internet can compromise these advantages quickly. In a wired world, due diligence requires property owners, developers, lenders and securities analysts to investigate how quickly merchandise and customers migrate online. Not to do so results in only seeing half the picture. In the future, one needs to ask: Dealing with Change. Online buying will not make stores redundant. However, Egghead’s transformation into an online retailer and Amazon.com’s high market capitalization are harbingers. They point to a radical change in merchandising unconstrained by space. This reminds us once again that retailers are merchandisers first and location acquirers second. In other words, where they sell is less important than what they sell. The nature of online buying as a convenience channel will motivate mass market merchants to undertake sales channel reformation. If the store is no longer the predominant platform for merchandising, then retail property investors must also question the fundamental premise of location, location, location. (5/16/98)

1 The Consumer Internet Economy, Gene DeRose, Chairman

and CEO, Jupiter Communications, June 3, 1998.

**Mark Borsuk (mborsuk@ix.netcom.com) is Managing Director of The Real Estate Transformation Group, a firm advising landlords, retailers and lenders on strategies for the information age. In addition to consulting, Mr. Borsuk is a retail leasing broker and real property attorney practicing in San Francisco. He has written extensively on the structural change in retail space demand induced by the integration of computer hardware, software, networks and telecommunications into daily life, which he terms INFOTECH. His ideas on INFOTECH’s impact have appeared in Discount Store News, Journal of Applied Real Property Analysis, Pensions & Investments, Real Estate Review, Shopping Center Business and Urban Land. Many of his articles are on the Web. Prior to entering real estate, Mr. Borsuk was a foreign exchange trader and currency advisor in Tokyo and New York. Speaking and reading Japanese, he pioneered in the analysis of the Tokyo foreign exchange and money markets. His research appeared in many financial journals including Euromoney and the Asian Wall Street Journal. Mr. Borsuk holds an MBA from Sophia University (Tokyo), a Japanese language certificate from Nichibei Kaiwa Gakuin (Tokyo) and a law degree from Loyola University (Los Angeles, Law Review). ***Copyright © 1998. Mark Borsuk. All Rights Reserved, except the reader may copy this article into electronic form or print for personal use only, provided that: 1) the article is not modified; and 2) all such copies include this copyright notice. News Releases | Articles | Upcoming Talks | Memorable Quotes Copyright ©1995 - 2020. Mark Borsuk. All rights reserved. Disclaimer notice |